Cmu Museum of Art Hall of Architecture Good Four Color Combinations

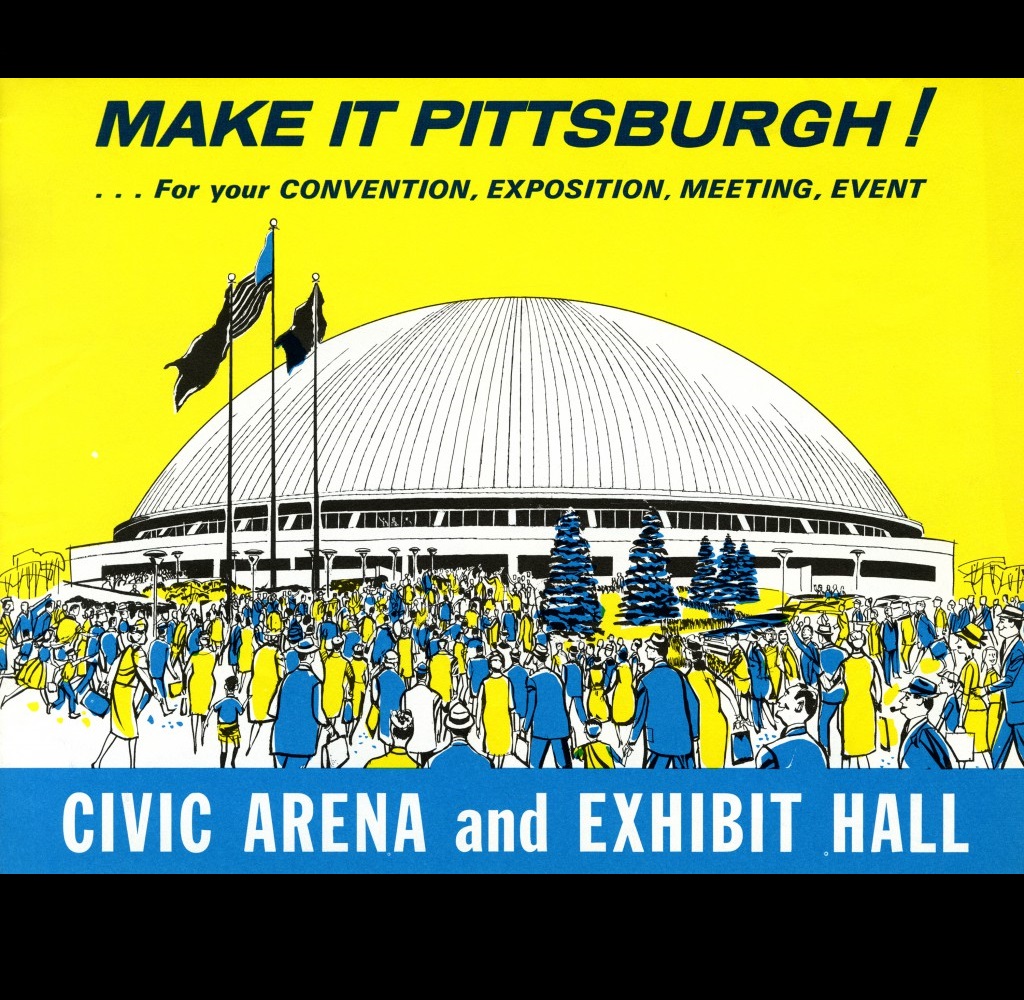

The Public Auditorium Say-so of Pittsburgh and Allegheny Canton; Make It Pittsburgh! (brochure), c. 1961; Borough Arena; Mitchell & Ritchey, architect; Courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University Architecture Athenaeum

Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh; Helmut Jacoby, renderer; Illustration from Allegheny Center: From a Rich Heritage, a New Way of Life… (brochure), c. 1962; Allegheny Center; Deeter & Ritchey, builder; Courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University Architecture Archives

Past Roslyn Bernstein

For a native New Yorker, the geography of Pittsburgh is something of a challenge. We are conditioned by our urban center: uptown is north and downtown is south. In Pittsburgh, though, if yous study the map, uptown is east and downtown is west and the tangle of three rivers—the Monongahela and the Allegheny converging to form the Ohio River—results in a hilly landscape of North Side and North Shore and South Side and South Shore neighborhoods, connected by 446 bridges, more than Venice, which simply has 409.

Known every bit "The Urban center of Bridges" and "The Steel City," Pittsburgh saw early on and rapid industrial growth in the downtown area and forth the riverbanks that strengthened its economy only resulted in citywide ecology and social catastrophes. Near notable among them was the nighttime fume that hung over the city, keeping out the sunlight and roofing everything, buildings and people alike, with a layer of soot.

After World State of war Ii, Pittsburgh politicians, civic leaders and architects embarked on a brave programme of urban revitalization. For ii decades in the 1950s and 1960s, they turned their lens on urban planning and architecture, convinced that only an alliance of the three forces could save their town. The result of their efforts, the Beginning Renaissance era, transformed vast sections of the city, serving equally a model for development of many other U.s.a. cities, including Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and New York.

Pittsburgh proved to be a leader, providing a modernist template for other American cities that sought to reverse the flight to the suburbs, which resulted in population decline and loss of tax revenues in the city centers. With help from the federal authorities, urban renewal projects sprouted upwardly in vast areas of the urban center—in The Point, the Golden Triangle, the Lower Hill, Allegheny Center, Oakland and East Freedom. Under the leadership of Mayor David L. Lawrence and broker Richard King Mellon, industrial buildings at the prime real estate where the 3 rivers converged were demolished and Point Land Park was built. New highways and parks contradistinct the infrastructure, and new buildings, mostly commercial just too civic and residential, transformed the architectural landscape. The Renaissance did not stalk the flight to the suburbs, just it did create a vibrant commercial and civic urban center. From the mid-'70s through the '80s, nether Mayor Richard S. Caliguiri, a second Renaissance saw the development of many large corporate skyscrapers. Today, spurred by the growth of the Tech and Wellness Care industries, the city is again seeing a flurry of construction activity, much of which is bringing residents back to the center city.

Why not make a couple of exhibitions that are laboratories, he thought. Why non cull a actually big subject: Post War Urban Modernism?

I start came to Pittsburgh a few months ago with my husband, who is part of a group with Crow Hill Evolution of Brooklyn that has purchased the old Boys' and Girls' Club in the Lawrenceville neighborhood, and is in contract to buy iii function buildings, including the 1958 Enquiry Facility, function of the erstwhile Heinz part and factory circuitous on the North Side. It was and then that I heard of the show at the Carnegie Museum of Fine art exploring the urban renewal movement and modernist compages of the metropolis.

An investigation of Pittsburgh'due south post-war transformation—its post-war urban modernism, which was lauded at the time but which has had a contentious history and has sometimes been less than successful—was very much on the listen of Raymund Ryan, Curator of the Heinz Architectural Heart (HAC) at the Carnegie Museum of Art (CMOA). After 12 years of exhibiting three traditional shows annually in the 4,000 foursquare-foot dedicated space, Ryan wanted to milkshake things up and "get off the treadmill." His goal was to try to be more engaging, more assertive, and more proactive. Why non brand a couple of exhibitions that are laboratories, he thought. Why not choose a really large subject: Postal service State of war Urban Modernism? Why non run the HAC Lab nigh eight months, from September 12 to May 2?

Ryan decided to bring in folks who knew how to do this: an innovative squad of Boston-based architects and designers, over, under, who had done an exhibit and written a book, HEROIC, on the concrete architecture of mail service-war Boston. The squad, including principals Chris Grimley, Michael Kubo, and Rami el Samahy, worked with Ryan and with Martin Aurand, the Architectural Librarian and Archivist at Carnegie Mellon Academy (CMU) to research, blueprint, and install the show. Their thrust: to unearth what happened in layers, creating an exhibit that was intended equally an archeological dig into the archives and artifacts of the urban center's modernism and to provoke word on what worked, what didn't, and what should be done moving forward.

"Maybe nosotros are only contrarians," said Rami el Samahy, who is also an Associate Teaching Professor at CMU, "but we merely like to encounter things that people hate, run into the modernist layer as one of the layers." We were walking through the showroom, watching the final flurry of installation activities before its evening opening. El Samahy explained that there have been two main historical critiques of urban modernism, first, that it is "plain ugly and inhospitable for human habitation," and second, that "urban planning eviscerated the traditional city fabric." "In Pittsburgh," he said, "some of the infrastructure that was inserted created problems for normal folks to go about their lives."

As a radical difference, the HAC Lab show has three entrances, doors decorated with vinyl decals of tripods, and tin be viewed in any order. Two of the doors open up from fine art galleries at either end of a long corridor. The third, from a mezzanine in the Hall of Sculpture, leads into a short corridor intersecting the long corridor. One opening in the curt corridor connects to the Lab room. On the other side, an opening leads to three interconnected rectangular galleries.

In the long corridor, the West Wall (installed on a blue background), provides an introduction to the national context of urban renewal in the postwar era. The wall focuses on major interventions that are grouped according to biological metaphors for the metropolis: its transportation and infrastructure as "Lungs and Arteries," its civic and cultural spaces "The Heart of the City," and neighborhoods with new housing are the "Cells and Tissue." Noted here, are St. Louis's "4 vast housing projects," including the notorious Pruitt-Igoe development, which opened in 1955 and was demolished starting in 1972, forth with other efforts in Pittsburgh in East Freedom, Allegheny Heart, and the Colina District.

Prominently featured in the eye of this wall are two Pittsburgh urban renewal documents. The first is Pittsburgh in Progress (1947), sponsored by department store magnate Edgar J. Kaufmann. Kaufmann was a major patron of modernistic architecture in Pittsburgh; he deputed Frank Lloyd Wright'due south Bespeak Park proposals (which were never built) and brought in Robert Moses to assist plan the highways in 1939. Produced by the local architectural firm of Mitchell and Ritchey, even the graphics of the brochure spoke to its modernist sensibility. Featuring space-historic period renderings, information technology envisioned a metropolis filled with modernist high-rises, acres of park space, and a monorail organization, with major urban renewal development projects for the Lower Hill, Point Park, the Northside (afterwards Allegheny centre), and Panther Hollow.

On the panel reverse Pittsburgh in Progress is a 2nd certificate from the same year: Pittsburgh—Challenge and Response, which described the goals of the Allegheny Briefing on Community Evolution, chaired past Richard Male monarch Mellon. Different the more modernist more visionary thrust of Pittsburgh in Progress, Pittsburgh—Challenge and Response had specific answers to the "problems of fume, blight, housing garbage, pollution, colorlessness, traffic congestion, and floods."

"Information technology was all washed for suburbanites who never came."

On the East corridor wall, the background is cherry and the focus is on urban renewal and modernism in Pittsburgh. In the middle of the wall is a current map of Pittsburgh with six neighborhoods highlighted as study areas: The Signal, The Gilt Triangle, Lower Hill, East Liberty, Oakland, and Allegheny Center. Side by side panels illuminate evolution in each of the areas. Point Land Park and the Gateway Eye opened in The Point, which was also home to the IBM Edifice and the steel Westinghouse Building. In Pittsburgh's downtown Gilded Triangle, modernist buildings included the Alcoa Edifice and two US Steel buildings, each designed by Harrison & Abramovitz. In Lower Hill, land was cleared for the construction of the Civic Arena, which proved to exist a failure as a cultural mecca and was demolished in 2011. Urban redevelopment in Oakland reflected the expansion of the Academy of Pittsburgh. One massive project that never happened was Panther Hollow, a proposal to fill in an unabridged ravine situated betwixt Pitt, the Carnegie Museums, and Carnegie Tech. In East Liberty, the Urban Redevelopment Say-so (URA) played a prominent role in reducing traffic congestion and in improving housing stock.

Adjacent to the map are three diagrams, based on extensive enquiry by Carnegie Mellon architectural historian Martin Aurand. These nautical chart built, unbuilt, and demolished projects from the years 1945 -1975, connecting them through white lines to their architects and to their corporate, institutional, and civic sponsors. While many of the civic projects accept since been demolished—including the original Pittsburgh airport, the Civic Arena, and the Children'south Zoo. Significantly, none of the corporate projects, including the Alcoa Edifice, the HJ Heinz Vinegar Institute (1952), the Heinz Warehouse (1975), and the Riley Research Center (1958), accept been torn down. Most of the institutional buildings erected in the 1960s, sponsored by Carnegie Tech, Carnegie Mellon Library, and Allegheny Community College, are also withal standing.

The almost unique part of HAC Lab is the lab itself. Accessed from the long or curt corridor, the room is filled with desks arranged in a tripodal pattern reflecting the 3-office freestanding structures holding some of the exhibit materials. In this room, el Samahy'due south third and 4th year architectural students will run into and work on rethinking the Allegheny Center, which was a prime example of the failure of urban renewal and sits largely abandoned. The North Side of Pittsburgh, originally known as Allegheny City (an independent city) was annexed to Pittsburgh in 1907. Throughout the 1950s, information technology suffered from high crime, and was filled with derelict structures. The population declined past 25 percent. Many buildings in its historic core were razed in the years 1965-1973, and the urban renewal design programme for the surface area, Allegheny Heart, called for building a four-lane, 1-way loop of a highway effectually the neighborhood, with a shopping mall and hush-hush parking.

"Information technology was all done for suburbanites who never came," said el Samahy, adding that "the highway cut off the centre from surrounding neighborhoods." The students' charge is to develop contemporary design proposals for Allegheny Center. El Samahy sees his students' efforts equally near a operation slice. "The public will be invited to come up in while the class is in session and their comments will be welcome," he said.

The layers of architectural modernism in Pittsburgh are scrutinized through photography, media documents, and picture.

One wall of the room is hung with historic drawings of the urban renewal era including original Frank Lloyd Wright drawings of the Point Park proposal. The other three walls are lined with Homasote, where the students will hang their work-in-progress.

The three other rooms in the exhibit peel back the layers of architectural modernism in Pittsburgh by scrutinizing photography, media documents, and picture. Organized co-ordinate to the perspective of different lenses, the photography room shifts from formal to informal: from the renowned architectural photography of Ezra Stoller, to the documentary photography of W. Eugene Smith, who arrived in Pittsburgh in 1955 after leaving Life Magazine, to Roy Stryker, the Data Manager for the US Subcontract Security Administration during the Depression, who documented the Pittsburgh Renaissance with a squad of 11 photographers in the 1950s, and the local Brady Stewart Studio. Also on view is the community photography of Charles "Teenie" Harris, a local photo-announcer whose photo exhibit on cars is currently being shown in the Carnegie Museum of Art, and images shot by Troy W, whose camera focused on the Hill District, the eye of African American life and of jazz in Pittsburgh. "At first, the African American community was very supportive of plans to develop the Hill," el Samahy said. "Then they realized that they were not getting what they wanted. Overall, ane of the biggest shortcomings of urban renewal was that not enough federal dollars went to housing."

Early in the morning, the document room was filled with people wearing rubber gloves. Along the summit of each wall, like a Greek frieze, was a timeline of the pop press, copies of local stories from prominent Pittsburgh newspapers. "Ideal Housing Believed Possible if Pittsburgh Enforces Slum Laws," reads the headline from the Pittsburgh Postal service-Gazette of Jan 24, 1934. "City of Pittsburgh'south Housing for Negroes: Is the Hill District Doomed?" reads the negative headline of the Pittsburgh Courier from April 29, 1950. "Allegheny Middle… Renaissance on the North Side," is the headline from a Pittsburgh Printing story of May 19, 1963. "Does Urban Renewal Mean Negro Removal?" is a bold headline from the Pittsburgh Courier of Baronial 7, 1965.

Beneath the timelines of popular printing stories are pieces from the architectural press, including the earliest commodity on Pittsburgh urban renewal in Architectural Forum, from November 1949. These do not marshal chronologically with the popular press stories in a higher place. Rather, almost are positive features on Pittsburgh's modernist move. One headline sums them up: "An urban redevelopment dream is coming truthful in Pittsburgh," reads the headline in the Engineering News Record for April 24, 1952.

A flakeboard cabinet, designed for the exhibit by Chris Grimley, has drawers belongings issues of Architectural Record, Industrial Design, and Interior Pattern as well as books on landscape architecture. "Some," el Samahy admitted with a grinning, "were actually purchased on eBay." Another case features manifestos, essays, and promotional brochures. Prominent amongst them is Brand It Pittsburgh!, a bold blue and yellow advertisement for the at present-demolished Civic Loonshit.

In the third room, half dozen documentary films from 1939 to 1962 are shown in a loop. All characteristic themes relevant to the exhibit; some from a national perspective, some focusing on Pittsburgh's urban renewal, and some highlighting developments in other The states cities. "We chose these films considering they reflect the full general tenor of discussion in the postwar era, or at to the lowest degree the voices with admission to film and tv set production," el Samahy said.

While the films will alter over the class of the exhibit, the electric current listing includes a 21-minute blackness-and-white film from 1939'south Housing in Our Fourth dimension, sponsored by the United states Housing Dominance of the Federal Works Agency, a 27-minute black-and-white film from 1955, Freedom of the American Road, sponsored by the Ford Motor Visitor, a 28-infinitesimal color movie from 1956, The Dynamic American City, sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce of the Us, and a 28-minute color moving picture from 1962, Grade, Design and the Metropolis, sponsored by the Reynolds Metals Company in cooperation with the American Institute of Architects.

Experiencing the 3 rooms, says Rami el Samahy, is akin to feeling the parts of an elephant when you are blindfolded. "One tin only hope that, for the viewer, it will all come together as the elephant."

I exited the HAC Lab show through the middle entrance, where iv artists' visions of Pittsburgh hang on the walls. There's Pop artist Claes Oldenburg'south vision of the Golden Triangle covered with sixteen billiard assurance and ii color photos past Walter Seng of artist Otto Piene'due south sky ballet, sculptures made of balloons. There's Pittsburgh photographer Ed Massery'due south two photos of the final days of the Civic Loonshit, and, there's master photographer Ezra Stoller's handsome black-and-white portrait of the H.J. Heinz Research Facility, designed by Gordon Bunshaft for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1958. Coincidentally, looking through the glass wall of the Florence Knoll-designed antechamber, ane sees a large landscape by creative person Stuart Davis which tin can currently exist found hanging in a contemporary art gallery adjacent to the showroom. H.J. Heinz no longer has its enquiry facilities and central offices there, but the glass curtain-walled building, six stories on a base of two, remains, awaiting reimagining.

Roslyn Bernstein reports on arts and culture for such online publications as

At Guernica, we've spent the last 15 years producing uncompromising journalism.

More than 80% of our finances come from readers like you. And we're constantly working to produce a magazine that deserves y'all—a magazine that is a platform for ideas fostering justice, equality, and borough action.

If yous value Guernica'due south role in this era of obfuscation, delight donate.

Help us stay in the fight past giving here.

Source: https://www.guernicamag.com/roslyn-bernstein-museum-as-laboratory/

Post a Comment for "Cmu Museum of Art Hall of Architecture Good Four Color Combinations"